Soon after I began to cover fluid power back in the mid 1990s, I heard the drumbeat from many worried hydraulic component manufacturers — the electrics are coming to get us. There was a lot of fear (as well as a lot of doubt in some corners) that someday, electric actuators would replace hydraulic cylinders.

Soon after I began to cover fluid power back in the mid 1990s, I heard the drumbeat from many worried hydraulic component manufacturers — the electrics are coming to get us. There was a lot of fear (as well as a lot of doubt in some corners) that someday, electric actuators would replace hydraulic cylinders.

When that day would arrive, if ever, was a great topic to get engineers talking about over drinks after a long day at a trade show. One side would point to the fact that physics is physics, and hydraulics’ incredible power density would never be replaced, especially on mobile machinery. The other side would grumble nervously about all the strides electric actuators had made over the years, not to mention advances in batteries, and even point out individual applications, such as a particular airplane, where electrics were gaining traction.

Because of that, I suppose, hydraulics people of a certain age tend to think of any word like “electric” as a bit of a bugaboo. But who would have thought that the future might turn out to be a different one — one where hydraulics and electronics would get together in sort of an unexpected romance? And a wonderful romance at that, where each is greater than the sum of their parts, ushering in a promising new day for mobile hydraulics.

A recent users conference in suburban Chicago, put on by component manufacturer Bosch Rexroth, provided some interesting glimpses into this promising new union. Following are some things to watch for in tomorrow’s electrified mobile hydraulics.

It’s all about the software

Dr. Jonathan Meyer, Control Systems Engineer, explained that many companies are focusing on the challenges that we have today with the workforce. There are fewer workers, many of them are not experienced, and they are very used to technology, having grown up with mobile phones. How can we make mobile equipment something that’s intuitive to use? What’s more, there are different markets worldwide and different users may expect the machine to operate in different manners. Maybe one user wants a more aggressive handling technique, while another user wants the equipment to function in a more relaxed and precise manner. This is all compounded with inflation and cost pressures, as well as a desire for efficiency.

“Let’s look at a standard hydro mechanical machine that we have today,” said Meyer. “We have the hydro mechanical control pump, we have pilot-operated joysticks. We have hydromechanical valves. We have hydraulic hoses — and all of this requires installation effort, as well as hardware. ‘Set it and forget it’ could the tagline for hydraulics. But does it have to really be that way? Or can we get more flexibility in the system?”

Meyer said that electrohydraulic solutions will provide more functionality and efficiency and remove barriers — all from moving things more into software as opposed to on the hardware side.

The first step is the pump. They have created electronic open circuit (or EOC) pump control. This is not just software, Meyer said, but a combination of hardware and software.

“We have developed pumps specifically for this application, where we can integrate the control of the pump with the software and sensors on the machine to give us more performance than we have today with less complexity,” he said.

With hydromechanical controls, Meyer said that currently, we must mechanically adjust the settings — such as different pressure control options. By going to more of an electronic control architecture, that’s taking all those hardware variants and moving them into software, gaining flexibility. Now, you can have one pump for all of your machines and you’re able to set those settings however you want — specific to that machine, specific for the region that you’re sending it to, and specific to how the user wants it to operate.

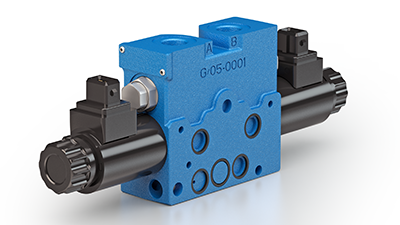

Another example he gave is in valves. Now, machine operators can take off the hydromechanical valves and replace them with an electrohydraulic valve. Then the software is what controls the entire system, for added flexibility.

Another example he gave is in valves. Now, machine operators can take off the hydromechanical valves and replace them with an electrohydraulic valve. Then the software is what controls the entire system, for added flexibility.

“One function that can be moved into software is flow management,” he said. “For example, standby flow management — currently that’s set by a mechanical setting you have to change on the flushing valve. We can replace that with an electronic flushing valve, and we’re able to reduce the standby flow. Plus, it is nothing that is fixed to a specific user or to a specific machine.”

Safety is key

“There’s that old saying that once you fall in love with hydraulics and get some oil in your blood, that’s it — you’re in it for life, and I think I’m going to be a lifer,” said Jean Pierre Zola, Business Unit Leader – Compact Hydraulics North America, Bosch Rexroth. “Now, machines are growing more and more sophisticated. Our customers’ expectations are higher, and there’s more focus on efficiency, and more focus on safety, too — because the number of skilled operators is very low here in the United States.”

Oftentimes, automation means less human interaction, such as what’s seen in autonomous vehicles — be they automobiles, huge mining trucks, or agricultural equipment. But when these vehicles are being used in somewhat close proximity to workers, defining a zone of safety is paramount.

Meyer noted that if you look at the amount of coding effort that’s spent per feature, Rexroth saw this growth going up exponentially. From 2010 to 2016, that factor went up by almost a factor of three.

“We had to put in three times the amount of effort in each one of those features that we had in 2010. And they weren’t just functional features. They were also the non-functional, the safety, the testability, the scalability features,” he said.

Meyer explained that legislative requirements, functional safety requirements, noise requirements, and emission requirements all come into play here. But as safety standards change across time or location, it’s not in any customer’s best interest to have to start from scratch. With the new control software available, customers are able to set the dynamics, set different drive modes, set different HMIs — all within the parametrization. The software meets functional safety standards. That means zero costs — they don’t have to have software engineers who are developing over and over.

New components are coming

According to Peter Braun, Sales Director, having a bigger engine in mobile machinery is not necessarily helpful anymore, and smaller engines of course result in less available power. Trends are being driven by material regulations or the Stage V emission standards in Europe — there, manufacturers are seeing a continued trend of downsizing of the diesel engine and the downsizing of the available engine power. That all means new components are needed, and electrification is the wave of the future.

According to Peter Braun, Sales Director, having a bigger engine in mobile machinery is not necessarily helpful anymore, and smaller engines of course result in less available power. Trends are being driven by material regulations or the Stage V emission standards in Europe — there, manufacturers are seeing a continued trend of downsizing of the diesel engine and the downsizing of the available engine power. That all means new components are needed, and electrification is the wave of the future.

One example of the new generation of components is the Rexroth’s eLION range of electric motor-generators, inverters, and accessories. The line also contains tailored gearboxes, hydraulics, and software. These components, specifically designed for the challenging environmental conditions of off-highway applications, are scalable, with a nominal power range from 20 to 200 kW for driving and work functions.

The eLION range was introduced last September in Germany, and the company said production on the components is starting in 2022. Pilot projects have already been conducted with OEMs that include Kalmar and Sennebogen. Matthias Kielbassa, VP Electrification, emphasized the three most important properties of the new product platform are scalability, robustness, and functional safety.

The product family’s electric 700 V eLION motor-generators deliver nominal torques of up to 1050 Nm and maximum torque to 2400 Nm. They are available in four sizes with different lengths and winding configurations. Depending on the design, they are available in a fast or standard-speed version. The company said that more than 80 configurations are possible, for maximum design freedom for manufacturers when electrifying existing and new vehicle architectures. To accompany the range of motors, eLION also includes inverters in various power classes with up to 300 A continuous current and high overload capacity. The inverters support DC bus voltages from 400 to 850 V.

Gearboxes with high power density for hub and central drive configurations (eGFT and eGFZ) are also part of the eLION portfolio and allow compact drive units for a wide range of applications. BODAS software modules are available for the entire eLION platform, along with matching hydraulic components such as axial piston pumps. And other electrical components such as DC/DC converters, power distribution units, on-board chargers and high-voltage cables round off the range. Manufacturers can rely on these integrated solutions regardless of the energy source (such as hybrid or battery).

Possibilities across segments

“Once you have electronified your machine, there are basically endless possibilities — you can incorporate our virtual measurement unit with our kinematic resistance software, and we’re able to perform, for example, easy grade functions on machines,” said Meyer. “We’re able to create virtual walls, joystick steering … and this is scalable in everything. You can choose to electrify just the pump or you can electrify the whole system. You can add advanced assistance functionalities at any time, and you can use this with any end-engine technology. And we can use this in any compact segment there is today.”

Filed Under: Fluid Power World Magazine Articles, Mobile Hydraulic Tips