By Josh Cosford, Contributing Editor

We don’t hear much anymore regarding sequence valves, and probably for good reason. A sequence valve is like a self-regulating inline relay that opens when work pressure overrides the spring setting. It’s a form of hydraulic automation that provides sequential operation for two or more functions using one fluid supply source. However, with the proliferation of inexpensive automation and control systems, you can literally program a PLC on your phone to operate two directional valves quite easily. This begs the question: are sequence valves obsolete?

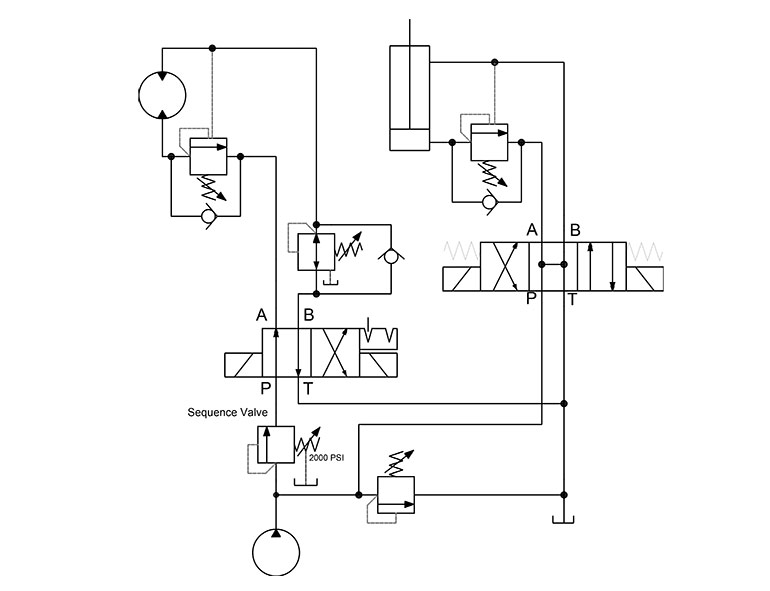

Sequence valve circuit

In the example hydraulic circuit, you can see I’ve placed a sequence valve just after the pump and branched to the primary work line with the relief valve and the cylinder subcircuit. When the pump starts, the path of least resistance is through the open center directional valve and straight to tank. When the directional valve actuates to power the cylinder, hydraulic pressure rises to load pressure, which, for the example to work, must be less than the 2,000 psi setting of the sequence valve.

This particular circuit is an example of a clamp and drill function, so the cylinder will bottom out on the load before it arrives at the end of the stroke. When the cylinder stops, pressure rises until at 2,000 psi, the sequence valve opens. Like many pressure valves, the sequence valve operates like a relief valve. Indeed, a sequence valve is a relief valve with a spring chamber drain that allows pressure to bleed when both work ports are simultaneously exposed to pressure. Without such a drain (or vent), the spring chamber could fill with pressurized oil, subsequently increasing the spring force or locking it altogether.

Sequence valves from Walvoil still have many uses in opening a secondary circuit line.

The location of this sequence valve negates the need for a reverse flow check valve. The check valve allows free flow in the opposing direction, which is beneficial when placed in the work ports of the actuator, as there is no backward flow path through the valve. Sequence valves are handy for creating a secondary function on existing systems, such as a tilt function to a bin lift or a locking pin on a tailgate lift.

As mentioned, sequence valves require a drain port, so you’ll see three ports on every inline sequence valve body. For integrated circuits (custom manifold blocks), the cartridge valves have three ports. Both spools and poppets may be used for sequence valves, although poppets tend to suit higher pressure applications better. Some valves used on low-duty applications may employ a vent rather than a full fledged drain port.

High-flow applications, like many large valves, are pilot-operated. When a sequence pilot valve operates a slip-in cartridge valve, hundreds of gallons per minute are possible. Most sequence valves offer a balanced piston, which provides stability despite the effects of flow forces or high-pressure differential.

Some of the “big guys” in the cartridge valve industry offer myriad designs and options of sequence valves. Despite the growth of microelectronic control systems or smart PLCs, nobody is obsoleting sequence valves any time soon.

Filed Under: Components Oil Coolers, Engineering Basics, Fluid Power Basics, Technologies, Valves & Manifolds