Image: istockphoto.com

Unique, easily changed designs dominate in agricultural machines, where the power density and the precision offered by electrohydraulics will continue to keep farms in the green.

The agricultural machinery industry has probably been the slowest evolving sector with regards to electronic integration. It’s not that machine manufacturers haven’t kept up to date with the latest technology; it’s more that the vast majority of farms (by principle owner, not acreage) are still relatively small. According to the 2012 USDA Census of Agriculture, of the 2.1 million principle ownership farms, more than 75% sold less than $50,000 per year, and about 57% sold less than $10,000 per year. This leaves little room in the budget for GPS-equipped combines, as you can imagine.

Hydraulics have been absolutely integral to farming since the invention of fluid power. Where industrial hydraulics replaced mechanical machinery, agricultural hydraulics replaced man and beast, saving both warm bodies from injury and increasing productivity exponentially. Because a tractor could and would be anywhere in the hundreds or thousands of acres around a farm, access to any type of electric power was non-existent. If you wanted something done, you needed mechanical motivation or old-fashioned blood, sweat and tears.

The advantage of agricultural hydraulics over many decades has been that they are strictly mechanical, having no reliance on even 6- or 12-V tractor electricity. Hydraulics are as easily understood as the PTO on the family farm’s tractor, can be replaced or jury-rigged in the field (literally … in the field). The single fixed-flow, open-center pump supplying flow to a single monoblock valve on 70-year-old Farmall is still something you can find in use on a field today. When machinery is that reliable, and your farm only pulled in $50,000 last year, how can you justify twice that amount for a new model with modern technology?

Unique designs

Wireless and electronic controls on farm machinery, such as this Kar-Tech Compact mini-bellypack wireless transmitter, are quickly becoming standard devices on hydraulic systems rather than optional functions.

Agricultural hydraulics are unique in many ways. Systems must be versatile and adaptable, because prime movers and supply of input hydraulics vary vastly. You could have a hydraulic pump driven from the PTO of the tractor, or use the hydraulic take-offs from the tractor itself. If the tractor hydraulics is used, it will be either “open center” (fixed displacement pump) or “closed center” (variable displacement pump).

The terms open center and closed center, when used to describe hydraulic valves, refer to the center condition of a directional valve. In the agriculture industry, it simply tells the user or designer that valving is either “pressure-to-tank” in neutral, or “pressure port blocked” in neutral. Which system is used affects the nature of the hydraulics on the implement. Although most of the industry has switched to closed-center, variable pump systems, there are still so many old tractors out there running open-center, fixed pumps. This is why designing machinery for the agriculture industry is so challenging; the one size fits all solution is rare.

To get a better idea of the difficulties in designing machinery for the agriculture industry, I spoke with Troy Grose, mechanical designer with Husky Farm Equipment in Alma, Ont., an agricultural OEM specializing in liquid manure processing systems. They build pumping, transferring and spreading equipment of various types, most using hydraulics.

Photo: istockphoto.com

Grose explained what makes agricultural hydraulic machines different from other mobile hydraulic applications. “When working with implement-style machinery (towed behind a tractor), the hydraulic solution supplied must be capable of adapting to any tractor that is connected with it. In many other mobile hydraulic applications, a fixed solution can be designed and implemented specific to that particular application,” Grose said. “Ag equipment differs in that way, as you never know what tractor is going to be used. We can see one tractor capable of supplying 18 gpm and another of 40 gpm. Smaller utility tractors and some older tractors will have open-center hydraulic systems while the newer, larger tractors will have closed-center, pressure compensated systems.

“The hydraulic solutions we provide on our equipment must be able to adapt to these always changing scenarios. The agricultural machine can operate in a fury of harsh environments, making the component selection and design a critical part of the engineering process for a long lasting and durable machine.”

Flexible designs are a must

The flexibility required so hydraulic systems can adapt to any tractor is possible and quite simple. I worked on one application with Grose that combined closed-center directional control and accessory valves, which could be operated from fixed or variable pumps up to 60 gpm. The circuit contained a load-sensing network fed into a single, large, load-sensing pressure compensator. Based on the required flow at each actuator, the compensator would send only the flow required (from 2-60 gpm) to the circuit, and dump the unused flow back to tank. It was essentially a load-sensing unloading circuit.

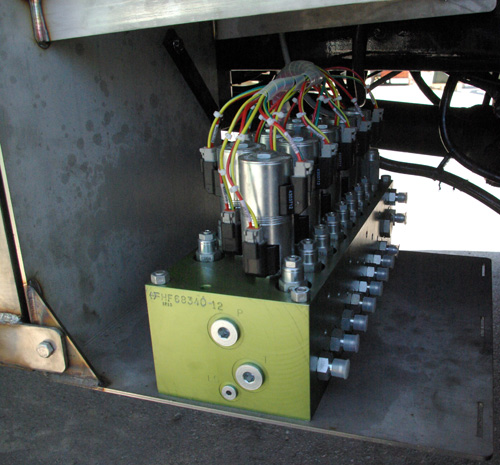

A close-up look at a hydraulic valve manifold for a Husky piece of agriculture equipment

Because you could load sense with a fixed pump, it would work with any pump, including a load-sensing pump. To convert to usage with a variable displacement pump, the compensator is simply removed and a cavity plug put into its place. This would negate the need for the load sense check valves, but they would not harm anything by being left in place. However, should a load-sensing pump be added as the supply, the load sense network could be tapped into from an auxiliary load-sensing port on the block. There was no hydraulic input below 60 gpm that this manifold could not have been used with.

Electronics are the wave of the future

I’m always curious where fluid power industries are going, especially with the changing global markets, so I asked Grose what he sees for the future of agricultural hydraulics, to which he responded, “Everyone in the ag industry knows what mono-block valve banks and tie rod hydraulic cylinders are, and those won’t be disappearing anytime soon, but we are seeing a shift to solutions that provide the operator with automated and easier to use systems,” he said. “Wireless control and electronic operation of these systems is undeniably already a dominant part but we will continue to see more equipment coming along with these installed as standard rather than optional features.”

Electronics have already proliferated in industrial applications and are quickly becoming a crucial part of agricultural machinery, too, albeit at a slower pace.

“Electronics have already become an integral part of the hydraulic system for us. We are supplying wireless remotes to control monoblock valves where the operator doesn’t have to get out of the tractor seat to operate other functions in a completely separate tractor,” Grose said. “In our mobile truck-mounted tank division we sell a hydraulic manifold that can adapt to any truck it is mated to with up to 60-gpm input flow, and all directional valves are controlled electronically by the operator in the cab. In this same application we are controlling the ramp up and down speed and maximum flow to hydraulic motors electronically; their values are adjusted electronically.

“We are also seeing a shift to GPS mapping systems where application rates are controlled electronically from the tractor. Tractors are able to use mapping systems and auto-steer to have their tractor drive exactly where they want it to go, and rate apply the product to the field all done with virtually no operator input once the setup is complete,” Grose continued. “These systems are integrated into the tractor through ISOBUS (ISO 11783), which is becoming a more standardized interface between implement and tractor. The standardization of interfaces like ISOBUS are a necessary part to ensure that all our implements can talk to each tractor regardless of what color the tractor is. With integrated systems between the tractors mechanical functions, GPS, hydraulics, and the implements it tows, there will be endless possibilities to where electronics are going to take us in the future.”

I firmly believe electrical actuators will never replace hydraulics on mobile machinery, but I also agree with Grose’s sentiment that electronics will have in increasing share of control function of hydraulics, whether they are on an injection molding machine or manure spreader. I also believe manually controlled hydraulics will have a home for decades to come, as farmers love to feel a mechanical lever under their gloved hands. So don’t put that Farmall in a museum just yet.

Image: istockphoto.com

Filed Under: Mobile Hydraulic Tips